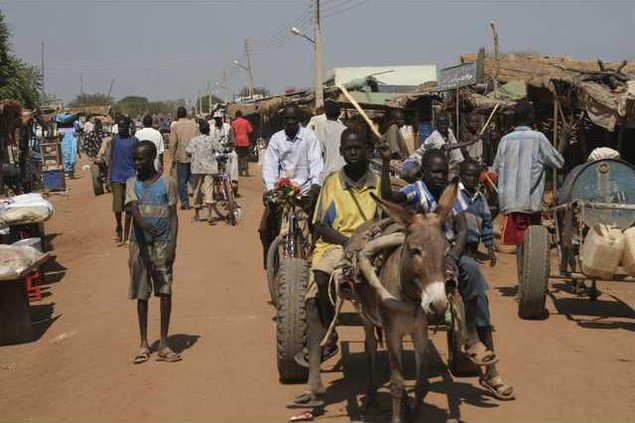

ABYEI, Sudan — This ramshackle town of mud huts and dirt roads is swarming with returning African refugees, Arab militiamen and rival troops from north and south Sudan — all eyeing each other in fear of a spark that could detonate the volatile mix.

Nearby lies a prize that all are eager to win: some of Sudan’s richest oil fields.

Claimed by north and south, Abyei has become a potential flashpoint that could wreck the fragile peace between the ethnic African south and Sudan’s Arab-dominated government in the capital Khartoum. The two sides made peace in 2005 after more than two decades of civil war.

A return to the war could plunge all of Sudan into chaos and exacerbate the separate conflict in the western Darfur region which has claimed more than 200,000 lives since 2003.

‘‘The only hope I have is that the fighting won’t be started by our side,’’ Bol Dau Deng, the local coordinator of the government’s Relief and Rehabilitation Commission, told The Associated Press, referring to southerners.

Deng is a southerner but is in a precarious position between the two sides. His commission, meant to help returning ethnic African refugees who fled the civil war, represents both the southern administration and the Khartoum government. With Abyei’s status unclear, he is by default the highest-ranking — and just about only — government official in the town.

Abyei lies just north of the boundary line between north and south Sudan set by Sudan’s British colonial rulers in the early 20th century. But the line is disputed, and southerners want the area incorporated into their autonomous zone, created by the 2005 peace agreement.

Many of the south’s former rebel leaders come from Abyei and frequently vow to reclaim the area. But the government in Khartoum, unwilling to let go of lucrative oil fields nearby, has rejected a proposed new boundary recently drawn by an international commission that would abut Abyei in the south.

The dispute has already shaken the peace deal once. Last October, southern cabinet ministers walked out of the unity government over a number of disputes, including Abyei — raising fears the peace could collapse.

The ministers rejoined the government in late December, having settled most of their differences — except for Abyei.

The 2005 peace deal was a rare, landmark success in Sudan, coming as the separate, though similar conflict in Darfur was escalating. In Darfur, ethnic African rebels rose up against the Khartoum government in 2003, sparking a conflict that shows no sign of ending. A new U.N.-African peacekeeping force was launched in Darfur on Monday, but many fear it will not be strong enough to stop the violence amid resistance from Sudan’s government.

If the north-south peace should collapse and fighting between the two sides resumes, the resulting chaos would likely intensify the conflict in Darfur as well.

For now, Abyei, 500 miles southwest of Khartoum, remains tense, with both sides jockeying for position. The area holds important oil reserves. The International Crisis Group estimates that oil fields in the area brought in about $670 million for Sudan in 2006, about 13 percent of its income from oil exports that year.

Since 2005, tens of thousands of ethnic African residents driven out by the war have flooded back into Abyei and its surroundings. They are returning from refugee camps farther south with the implicit backing of the southern government, which wants the area to vote in favor of the south in national elections planned for 2009.

The influx has catapulted the area’s population from nearly zero before 2005 to about 90,000 — the vast majority of them returning ethnic Africans from the Ngok Dinka tribe.

‘‘This is our home, we want to be here now that there is peace,’’ said Magig Toung Ngor, a Dinka chief in the nearby village of Dokra, built to host some of the returnees.

‘‘It’s important for our future,’’ he said.

A southern victory in Abyei in the 2009 election would then allow the town to choose independence from Khartoum along with the rest of southern Sudan in a referendum planned for 2011 under the peace deal.

The northern government, in turn, is counting on a tribe of Arab nomads known as the Misseriah, who graze their cattle around Abyei, to vote in the town and side with the north. But the Misseriah have splintered, with one armed militia from the tribe growing hostile to the Khartoum government and now supporting the southerners.

Meanwhile, hundreds of heavily armed southern and northern forces sit uneasily in and around the town, raising fears that friction could spark a new clash — or that one side or another could move to resolve the dispute by force.

Under the peace accord, all troops are supposed to withdraw from the border zone to allow it to be patrolled by 10,000 U.N. peacekeepers along with joint units of northern and southern forces. The two sides only began allowing the U.N. to patrol around Abyei in December.

But the northern army’s 31st Brigade, with 600 troops, remains in the town. Its commander, Brig. Gen. Abdel-Bagi Abdallah, says he has no intention of leaving until an agreement is reached on the north-south boundary.

The redeployment ‘‘will never happen, except if the president says so,’’ Abdallah told The Associated Press at the northern army’s barracks, one of the only modern compounds in a town otherwise made of a sprawling maze of mud and thatched huts known as ‘‘tukuls.’’

Abdallah insisted the situation in the town was ‘‘stable.’’

The former southern rebels from the Sudan People’s Liberation Army have a brigade posted some seven miles to the south. But many of its soldiers drift in and out of town to visit relatives.

Col. David Ogucholi, the ranking SPLA officer in Abyei, said it was ‘‘very, very important’’ that the Sudanese military pull back ‘‘to avoid incidents.’’

Amid the stalemate, there is effectively no government to provide services to the burgeoning population of refugees.

Deng’s commission is meant to do so, but it has little to offer. His office is empty except for a computer still in its packaging because there is no electricity.

The U.N.’s World Food Program feeds 19,000 of the returned refugees.

Nearby lies a prize that all are eager to win: some of Sudan’s richest oil fields.

Claimed by north and south, Abyei has become a potential flashpoint that could wreck the fragile peace between the ethnic African south and Sudan’s Arab-dominated government in the capital Khartoum. The two sides made peace in 2005 after more than two decades of civil war.

A return to the war could plunge all of Sudan into chaos and exacerbate the separate conflict in the western Darfur region which has claimed more than 200,000 lives since 2003.

‘‘The only hope I have is that the fighting won’t be started by our side,’’ Bol Dau Deng, the local coordinator of the government’s Relief and Rehabilitation Commission, told The Associated Press, referring to southerners.

Deng is a southerner but is in a precarious position between the two sides. His commission, meant to help returning ethnic African refugees who fled the civil war, represents both the southern administration and the Khartoum government. With Abyei’s status unclear, he is by default the highest-ranking — and just about only — government official in the town.

Abyei lies just north of the boundary line between north and south Sudan set by Sudan’s British colonial rulers in the early 20th century. But the line is disputed, and southerners want the area incorporated into their autonomous zone, created by the 2005 peace agreement.

Many of the south’s former rebel leaders come from Abyei and frequently vow to reclaim the area. But the government in Khartoum, unwilling to let go of lucrative oil fields nearby, has rejected a proposed new boundary recently drawn by an international commission that would abut Abyei in the south.

The dispute has already shaken the peace deal once. Last October, southern cabinet ministers walked out of the unity government over a number of disputes, including Abyei — raising fears the peace could collapse.

The ministers rejoined the government in late December, having settled most of their differences — except for Abyei.

The 2005 peace deal was a rare, landmark success in Sudan, coming as the separate, though similar conflict in Darfur was escalating. In Darfur, ethnic African rebels rose up against the Khartoum government in 2003, sparking a conflict that shows no sign of ending. A new U.N.-African peacekeeping force was launched in Darfur on Monday, but many fear it will not be strong enough to stop the violence amid resistance from Sudan’s government.

If the north-south peace should collapse and fighting between the two sides resumes, the resulting chaos would likely intensify the conflict in Darfur as well.

For now, Abyei, 500 miles southwest of Khartoum, remains tense, with both sides jockeying for position. The area holds important oil reserves. The International Crisis Group estimates that oil fields in the area brought in about $670 million for Sudan in 2006, about 13 percent of its income from oil exports that year.

Since 2005, tens of thousands of ethnic African residents driven out by the war have flooded back into Abyei and its surroundings. They are returning from refugee camps farther south with the implicit backing of the southern government, which wants the area to vote in favor of the south in national elections planned for 2009.

The influx has catapulted the area’s population from nearly zero before 2005 to about 90,000 — the vast majority of them returning ethnic Africans from the Ngok Dinka tribe.

‘‘This is our home, we want to be here now that there is peace,’’ said Magig Toung Ngor, a Dinka chief in the nearby village of Dokra, built to host some of the returnees.

‘‘It’s important for our future,’’ he said.

A southern victory in Abyei in the 2009 election would then allow the town to choose independence from Khartoum along with the rest of southern Sudan in a referendum planned for 2011 under the peace deal.

The northern government, in turn, is counting on a tribe of Arab nomads known as the Misseriah, who graze their cattle around Abyei, to vote in the town and side with the north. But the Misseriah have splintered, with one armed militia from the tribe growing hostile to the Khartoum government and now supporting the southerners.

Meanwhile, hundreds of heavily armed southern and northern forces sit uneasily in and around the town, raising fears that friction could spark a new clash — or that one side or another could move to resolve the dispute by force.

Under the peace accord, all troops are supposed to withdraw from the border zone to allow it to be patrolled by 10,000 U.N. peacekeepers along with joint units of northern and southern forces. The two sides only began allowing the U.N. to patrol around Abyei in December.

But the northern army’s 31st Brigade, with 600 troops, remains in the town. Its commander, Brig. Gen. Abdel-Bagi Abdallah, says he has no intention of leaving until an agreement is reached on the north-south boundary.

The redeployment ‘‘will never happen, except if the president says so,’’ Abdallah told The Associated Press at the northern army’s barracks, one of the only modern compounds in a town otherwise made of a sprawling maze of mud and thatched huts known as ‘‘tukuls.’’

Abdallah insisted the situation in the town was ‘‘stable.’’

The former southern rebels from the Sudan People’s Liberation Army have a brigade posted some seven miles to the south. But many of its soldiers drift in and out of town to visit relatives.

Col. David Ogucholi, the ranking SPLA officer in Abyei, said it was ‘‘very, very important’’ that the Sudanese military pull back ‘‘to avoid incidents.’’

Amid the stalemate, there is effectively no government to provide services to the burgeoning population of refugees.

Deng’s commission is meant to do so, but it has little to offer. His office is empty except for a computer still in its packaging because there is no electricity.

The U.N.’s World Food Program feeds 19,000 of the returned refugees.