JERUSALEM — Secretive real estate deals, hostility to priests, fist fights over Christ’s tomb, a power struggle between patriarchs — one of the oldest churches in the Holy Land is struggling to get through a moral and financial crisis, its leader says.

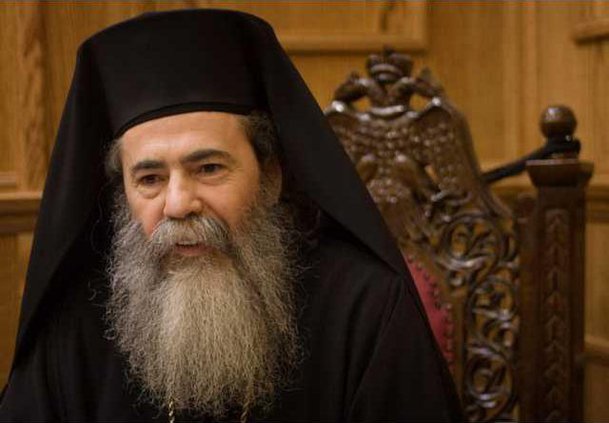

In a rare interview with The Associated Press, Patriarch Theofilos III says his Greek Orthodox Church in Jerusalem is in ‘‘the position of an acrobat,’’ faced by challenges on all sides.

The Orthodox Easter Week, which ends Sunday, was overshadowed again by squabbling. On Palm Sunday, Armenian and Greek Orthodox worshippers exchanged blows over rights of worship at Church of the Holy Sepulcher, built on the site where tradition says Jesus was entombed and resurrected.

However, Saturday’s holy fire ceremony at the Holy Sepulcher ended without trouble, even though some 10,000 pilgrims from different denominations crowded into the shrine. The patriarch said he had sorted out the dispute with the Armenians ahead of Saturday’s ceremony.

‘‘We don’t want to have more problems like this because they damage and destroy the image and the spirit of such events that are really very unique,’’ the 56-year-old patriarch said of last week’s fight.

In recent years, the church has been shaken by secretive real estate deals with Israelis, by Palestinian laymen angry about domination by Greek priests, and by a power struggle that reached an unusual climax with the ouster of an incumbent patriarch, Irineos I.

Theofilos, his rival, succeeded him in 2005. But not until December was he formally recognized by the three governments in the Holy Land — Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority. This Easter was the first in which he has led the rites unchallenged.

His flock of now 90,000 keeps shrinking, as do the other Christian denominations hit by emigration and relatively low birth rates. The patriarch is struggling to maintain a delicate balance among the church, its Arab congregants and the Israeli government. And he says he is trying to bring fiscal transparency to an institution that is the second largest landowner in the Holy Land after the state of Israel, yet chronically in debt.

‘‘The crisis that the patriarchate passed through, it was both moral, which was the most important, and of course financial,’’ he said. ‘‘There is no doubt about it. Now we are gradually recovering because order has been restored.’’

Irineos was ousted amid allegations that he leased two church-owned hotels in traditionally Arab east Jerusalem to groups trying to expand a Jewish presence there. The deal enraged his predominantly Palestinian flock, because Palestinians claim east Jerusalem as the capital of a future state.

Irineos has denied the allegations, and Theofilos has said he considers the leases invalid because they were never presented to the synod for approval. The dispute has since moved to an Israeli court.

The church would closely study all future transactions, he said. ‘‘We are not going to accept anymore the patriarchate to be treated as a real estate agency.’’

Israel only recognized Theofilos in December. During more than two years of rival patriarchs, Irineos refused to step down or leave his official residence. He has since been demoted to monk.

Theofilos said he would honor all transactions made with the state of Israel earlier, and new land leases would go through the synod.

‘‘The patriarchate ... emerges as a state within a state, as an entity, a very powerful entity, spiritual entity but it is an entity which lives on the ground and not in the clouds,’’ he said.

Theofilos tries to be diplomatic and non-confrontational in dealing with the governments in question, saying only that Israel’s long delay in ratifying his appointment was a ‘‘grave mistake.’’

The patriarch also has addressed complaints by Palestinian Christians of second-class treatment in the Greek-dominated church. An Arab clergyman has been appointed the spokesman of the patriarchate, a first. Theofilos promoted another Arab priest to archbishop. In the 18-member synod, where the vast majority of members are Greek, he finally filled a long-vacant seat reserved for an Arab.

Dimitri Diliani, a church member who was among those pushing to remove the previous patriarch, said Theofilos had walked ‘‘a thorny road’’ in a churchmanlike way, and his reforms had helped.

Before that, he said, ‘‘People were embarrassed to say they were Orthodox.’’

In a rare interview with The Associated Press, Patriarch Theofilos III says his Greek Orthodox Church in Jerusalem is in ‘‘the position of an acrobat,’’ faced by challenges on all sides.

The Orthodox Easter Week, which ends Sunday, was overshadowed again by squabbling. On Palm Sunday, Armenian and Greek Orthodox worshippers exchanged blows over rights of worship at Church of the Holy Sepulcher, built on the site where tradition says Jesus was entombed and resurrected.

However, Saturday’s holy fire ceremony at the Holy Sepulcher ended without trouble, even though some 10,000 pilgrims from different denominations crowded into the shrine. The patriarch said he had sorted out the dispute with the Armenians ahead of Saturday’s ceremony.

‘‘We don’t want to have more problems like this because they damage and destroy the image and the spirit of such events that are really very unique,’’ the 56-year-old patriarch said of last week’s fight.

In recent years, the church has been shaken by secretive real estate deals with Israelis, by Palestinian laymen angry about domination by Greek priests, and by a power struggle that reached an unusual climax with the ouster of an incumbent patriarch, Irineos I.

Theofilos, his rival, succeeded him in 2005. But not until December was he formally recognized by the three governments in the Holy Land — Israel, Jordan and the Palestinian Authority. This Easter was the first in which he has led the rites unchallenged.

His flock of now 90,000 keeps shrinking, as do the other Christian denominations hit by emigration and relatively low birth rates. The patriarch is struggling to maintain a delicate balance among the church, its Arab congregants and the Israeli government. And he says he is trying to bring fiscal transparency to an institution that is the second largest landowner in the Holy Land after the state of Israel, yet chronically in debt.

‘‘The crisis that the patriarchate passed through, it was both moral, which was the most important, and of course financial,’’ he said. ‘‘There is no doubt about it. Now we are gradually recovering because order has been restored.’’

Irineos was ousted amid allegations that he leased two church-owned hotels in traditionally Arab east Jerusalem to groups trying to expand a Jewish presence there. The deal enraged his predominantly Palestinian flock, because Palestinians claim east Jerusalem as the capital of a future state.

Irineos has denied the allegations, and Theofilos has said he considers the leases invalid because they were never presented to the synod for approval. The dispute has since moved to an Israeli court.

The church would closely study all future transactions, he said. ‘‘We are not going to accept anymore the patriarchate to be treated as a real estate agency.’’

Israel only recognized Theofilos in December. During more than two years of rival patriarchs, Irineos refused to step down or leave his official residence. He has since been demoted to monk.

Theofilos said he would honor all transactions made with the state of Israel earlier, and new land leases would go through the synod.

‘‘The patriarchate ... emerges as a state within a state, as an entity, a very powerful entity, spiritual entity but it is an entity which lives on the ground and not in the clouds,’’ he said.

Theofilos tries to be diplomatic and non-confrontational in dealing with the governments in question, saying only that Israel’s long delay in ratifying his appointment was a ‘‘grave mistake.’’

The patriarch also has addressed complaints by Palestinian Christians of second-class treatment in the Greek-dominated church. An Arab clergyman has been appointed the spokesman of the patriarchate, a first. Theofilos promoted another Arab priest to archbishop. In the 18-member synod, where the vast majority of members are Greek, he finally filled a long-vacant seat reserved for an Arab.

Dimitri Diliani, a church member who was among those pushing to remove the previous patriarch, said Theofilos had walked ‘‘a thorny road’’ in a churchmanlike way, and his reforms had helped.

Before that, he said, ‘‘People were embarrassed to say they were Orthodox.’’