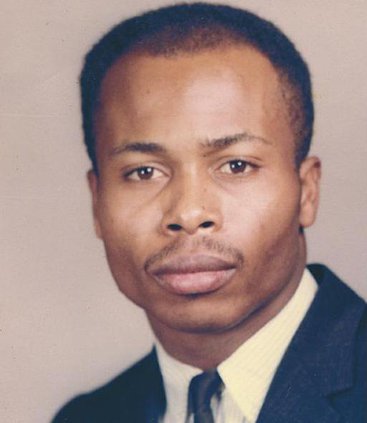

When John Bradley came to Georgia Southern in 1965, he had no intention of breaking the color barrier at the school. In fact, he wasn't even aware the school wasn't integrated.

But more than 40 years later, Bradley's contribution to the university resonates still as Georgia Southern University is one of the more racially diverse colleges in the country.

On Monday, Georgia Southern will unveil a plaque commemorating Bradley's place in Georgia Southern history followed by a luncheon in which several student leaders will have a chance to meet and listen to Bradley. The event begins at 11:30 a.m. with lunch to follow at the Russell Union Building. Despite being honored, Bradley said it really hasn't sunk in yet.

"Even now, it really hasn't hit me," he said. "Maybe when it happens, it'll hit me," he said.

Bradley was pursuing his Masters Degree in Chicago when he learned he'd need certain educational courses to be certified at the Masters level in the state of Georgia. He got in touch with the appropriate officials to ask where he could take the necessary classes. They told him Georgia Southern.

He said he wasn't aware Georgia Southern didn't have any black students, but knew something was going on when he went to register.

"The president and some other people escorted me and had me going around all the other students in line and I thought 'man, this is great,'" he said.

He said he later realized those escorting him were likely there for his protection in the event something happened.

"I don't recall filling out any forms having to do with race, so I don't know if they knew that I was black or not," he said.

@Subhead:Arriving on campus

@Bodycopy: When he began attending classes in January, he soon realized he was the only black student on campus.

"I don't think it was that noticeable at first because people may have thought I was a businessperson or someone there to visit the campus, but once they saw me with books, they started realizing that I was a student," Bradley said.

While in class, Bradley said he wasn't treated negatively by other students in the class. However, he wasn't treated positively, either.

In fact, they basically ignored him, Bradley said, choosing not to interact with him at all.

Different professors treated him differently, as well, he said. In one class, he expected to be the first person called on because of his race, but instead, the professor called on several other students before calling on Bradley.

In another class, Bradley said he made sure to type all of his papers and have others check it for grammatical errors while some white students would write it in ink. He would get a "B" or B+" while the other students would get an "A."

Local historian and former Georgia Southern professor Dr. Del Pressley said some faculty members didn't seem to want to teach Bradley.

"They didn't want to be the first teach of an African-American student as though it was some kind of badge of dishonor," Pressley said.

And while he was never physically assaulted, he did say he encountered his share of racism.

"On campus, I could here people calling me n------ from a distance," he said.

However, over time, Bradley said he began to see attitudes change among his classmates as they would begin speaking to him or give him a little smile from time to time.

"It wasn't being friendly, but I could feel a difference in how they treated me," he said.

Pressley said the turning point for Bradley came when he joined the Existentialism Club on campus.

"He finally found a group of compatible students and teachers who were interested in discussing those ideas," Pressley said. "They accepted him for his ideas and his intelligence."

Bradley went on to get his Ph.D. and today serves as director of the Augusta State University Conservatory Jazz Band, the Georgia Afro-American Jazz Band and the Richmond County All-County Jazz Band. Also, he is a former band director for the old William James High School. Bradley is married to the former Winnette Wesley of Statesboro and they live in Augusta.

@Subhead:Bradley's impact

@Bodycopy: After Bradley started in January, more black students began coming to Georgia Southern in the fall of 1965.

Unlike at the University of Georgia and in Mississippi, where there were dramatic clashes against the integration of the schools, Georgia Southern's transition was "pretty mild," Pressley said.

One of the reasons for that, he said, was the fact that Bradley came in January and was taking night classes, which was an advantage

Also, he credited then-Georgia Southern President Zach Henderson for making integration go as smoothly as possible.

"He was determined not to have a crisis," Pressley said.

Since that time, Georgia Southern has experienced a diverse campus that Georgia Southern political science professor Dr. Erik Brooks said "most places would die for."

In 1997, Georgia Southern's minority student population was 27 percent, the highest it has ever been.

"They discovered a congenial atmosphere and a relatively small campus when the transition occurred," Pressley said.

Pressley also credited the leadership of Dr. Dale Lick and Nick Henry for making a concerted effort to have a racially diverse campus and making sure it was comfortable for minority students.

Despite being the first African-American student at the school, Bradley still questions his impact.

"What did I really do? I went there, but 'Am I really that important? Was this really that significant?' I ask myself," he said. "By attending the school, a lot of students have been able to go and not feel a lot of the tension I felt."

"I'm proud that I was the first, but at the time it wasn't even on my mind," he said.

<I>Luke Martin can be reached at (912) 489-9454.

Georgia Southern to honor first African-American student

Plaque to be unveiled at Monday ceremony

Sign up for the Herald's free e-newsletter